Taiwanese Fried Chicken Cutlet

炸雞排 (Zha Ji Pai)

Taiwanese fried chicken cutlets (炸雞排)[1] are the humble main-course relative of the more famous Taiwanese fried chicken (popcorn chicken). In Taiwan, you will most often encounter these chicken cutlets, usually served with rice, an egg, vegetables, and some pickles, at…train stations? Yes, train stations. To understand why, we must turn once again to history.

In 1895, following the defeat of China in the Sino-Japanese War, the Qing Dynasty ceded the island of Taiwan to Japan. The island became Japan’s first overseas colony. At the time, about half Taiwan was populated by Han Chinese, with the other half ungoverned by China and inhabited by Taiwanese indigenous peoples. The two populations, historically at odds with each other, united in opposition to Japanese rule with a series of violent uprisings. Japan devoted significant military and political resources to pacify the island. The last major revolt, the Tapani uprising, was brutally crushed by the Imperial Army in 1915.

A contemporary Japanese woodblock triptych showing the Japanese invasion of Taiwan in 1895, during the Sino-Japanese War.

Japanese rule in Taiwan, however, did not consist solely of the stick. Japan established the Bank of Taiwan, and instituted compulsory primary education on the island. Japan also modernized Taiwan’s agricultural economy, turning it into a producer of large quantities of rice and sugarcane. In the aftermath of the First World War, with nationalist movements springing up around the world, many colonial powers moved to offer greater concessions to native peoples in an attempt to retain their empires. This trend, coupled with the democratization of Japanese government in the Taisho period (1912-1926), led to the rapid liberalization of Japanese policy in Taiwan. As restrictions on the population were loosened, and as education and the economy improved, public opinion of the colonial government began to improve as well.

A picture of the Taiwan Grand Shrine, a Japanese Shinto shrine built near Taipei in 1901. The shrine was demolished after the end of WWII, and is the modern-day Grand Hotel was built over the ruins.

Many Japanese liberals sought to turn the Taiwanese into full Japanese citizens (like many other colonial powers, the Japanese saw cultural integration as a positive and generous act, wiping away the “backwards cultures” of the natives). The local people were encouraged to learn the Japanese language, adopt Japanese names, and practice other elements of Japanese culture. Elections were held for local offices, and native Taiwanese politicians were even elected to the House of Peers of the Imperial Diet, Japan’s governing legislative body. Taiwan entered a period of stability and economic growth. In the 1930s, the island even saw an influx of Chinese immigrants from the mainland, seeking an escape from the political turmoil in China.

US Navy TBF Avengers and SB2C Helldivers of Carrier Task Force 38 strike targets on the island during the Battle of Formosa (Taiwan) in 1944.

The rise of a right-wing militarist government in Japan in the mid-1930s—a government which led Japan into first war with China, and then war with the United States—saw a severe contraction of the freedoms of the decade prior. Japan squeezed Taiwan for resources: rice to feed its population, fuel for the Imperial war machine, and men drafted to serve in the Army and Navy. As the demand for rice from the fighting front increased, there was no longer sufficient food for both local consumption and export. The food was shipped out, and the local population starved. In 1944 and 1945, with Japanese forces in retreat across the Pacific, the US Navy turned its attention to Taiwan. American carrier aircraft struck the island multiple times, hitting airfields, military installations, oil refineries, and infrastructure. Many Taiwanese fled the cities to escape the constant bombing, finding shelter in the mountains and waiting out the storm. At the end of World War II in 1945, Japan relinquished its sovereignty over Taiwan, turning the island over to the Republic of China.

50 years of Japanese colonial rule have left a mixed legacy on Taiwan. As in most colonies, the investments Japan made to improve Taiwan’s education, infrastructure, and economy were undeniably made to benefit the home country—either by improving the colony’s net economic output, or by pacifying the native population. Even under the liberal interwar regime, both Han Chinese and indigenous cultures were actively suppressed in the effort to turn the Taiwanese into full Japanese citizens. However, that the efforts made in the 1920s and early 1930s to culturally integrate Taiwan with Japan likely spared the island—at least to some extent—from the barbaric treatment of the subjugated peoples of other Japanese Imperial possessions (notably Korea and occupied China) during World War II. The culture of Taiwan still bears the influences of Japanese culture today—from school uniforms to cinema to baseball.

The Alishan Forest Railway (阿里山森林鐵路), a narrow-gauge line originally built during the colonial period to haul logs down from the mountains, still operates today as a heritage railway. It is one of the most popular tourist attractions on the island.

One of the more positive legacies of the Japanese colonial period is Taiwan’s extensive rail network. [2] Mainline railways were built to connect the island’s major cities and ports, with smaller lines branching out into the countryside and narrow-gauge snaking through the mountains. Nearly every Taiwanese town had a train station, no matter how remote. Initially built with the purpose of moving agricultural goods to the cities and ports for export, the railways also brought the people of Taiwan together. North was now connected to south, and rural Taiwan now had easy access to the rapidly growing cities. With the Japanese trains came Japanese-style train stations, and with the stations came bento boxes—complete meals sold in compact containers.[4] In Taiwan, bento became known as “bian dang” (便當). It’s not clear whether the Taiwanese fried chicken cutlet was a local take on Japanese katsu, or a pre-existing Taiwanese dish. In either case, it to fit well into the Japanese bento box tradition, and its popularity on Taiwanese trains took off.

A 700T train of Taiwan’s High-Speed Rail Network. Based on the 700 Series Shinkansen, the most noticeable difference is the 700T’s broader nose, aerodynamically optimized for Taiwan’s wider tunnels. The train also boasts a higher top speed and improved air conditioning.

After the end of World War II, under ROC rule and with significant American investment,[3] the rail network was repaired, and ridership continued to grow. Trains were the only means of long-distance transportation available to many Taiwanese for much of the 20th century. They carried mail to the countryside, goods to market, people to work, students to school, and soldiers to service. Most of these people traveling by rail would eat bian dang, a cheap and convenient meal on the go. Taiwanese bian dang evolved away from their Japanese counterparts, notably by doing away with separate compartments, and featuring local dishes. However, the core elements of the bento remained—rice, a chicken or pork cutlet, a braised or fried egg, and pickled vegetables.

Today, Taiwan still boasts one of the most robust rail networks in the world. While scooters and cars are now more widely available, trains are still an important part of the both country’s transportation system and its culture—trains bind the island together, and are a nostalgic reminder to many of simpler times. Taiwan’s love affair with rail travel continues—in 2007, Taiwan completed construction of a high-speed rail line running parallel to the old north-south main line. Perhaps fittingly, the system was derived from Japan’s Shinkansen. Railway bian dang are still very popular on these modern trains, with five million boxed meals sold annually at about $2 USD per box. If you’re ever traveling by rail in Taiwan, pick up a hot bian dang from the station for the authentic Taiwanese railway experience. If not, we can recreate one at home!

Ingredients

4 chicken breasts, butterflied

1 tbsp soy sauce

1 tbsp sesame oil

1 tsp cornstarch

1½ tsp white pepper

1 tsp flaky sea salt

1 egg

1 cup sweet potato starch

Vegetable oil

Begin by butterflying each chicken breast: holding the breast down with your non-dominant hand, carefully begin cutting it in half horizontally with a sharp knife, starting from the curved edge of the breast and working towards the flat edge. When you have almost reached the flat edge, stop cutting, leaving the two halves connected. Open up the chicken breast like a book. Then cover it with plastic wrap and pound the chicken with a meat mallet or a pot until it reaches a uniform thickness of ¼ inch. Don’t smash the chicken too hard, which can tear the meat—instead let the weight of the mallet or pot do the work for you.

In a bowl, make the marinade for the chicken by mixing together the soy sauce, sesame oil, cornstarch, and ½ teaspoon white pepper.

Carefully place the chicken cutlets in a large plastic zipper bag, and pour the marinade over the chicken. Press all of the air out to ensure contact between the meat and the marinade. Massage the bag so that the marinade is uniformly distributed, and all of the chicken pieces are coated. Set aside to marinade for 30 minutes to 1 hour in the refrigerator.

While the chicken marinates, prepare the pepper salt, a simple combination of flaky sea salt and white pepper. We want to be sprinkling it over freshly fried chicken while the chicken is still piping hot, when salt will adhere best, so it is a good idea to have a dish of it standing by.

When the chicken is ready to cook, prepare your breading station. In a bowl, beat together 1 egg with ½ a cup of water. The water thins out the egg, helping us achieve a lighter crust. Pour the egg mixture into a plate or pie dish, something large enough to lay a chicken cutlet into. On a second plate, place 1 cup of sweet potato starch. Most Taiwanese fried foods are breaded in sweet potato starch, which creates a very light and crisp exterior, less dense than flour or cornstarch dredges. It’s also a good idea to prepare a landing zone upon which we can put our fried chicken—I prefer to use a cooling rack placed on a sheet pan, to allow excess oil to drip off the chicken. Line the sheet pan with paper towels to absorb this oil and simplify the cleanup.

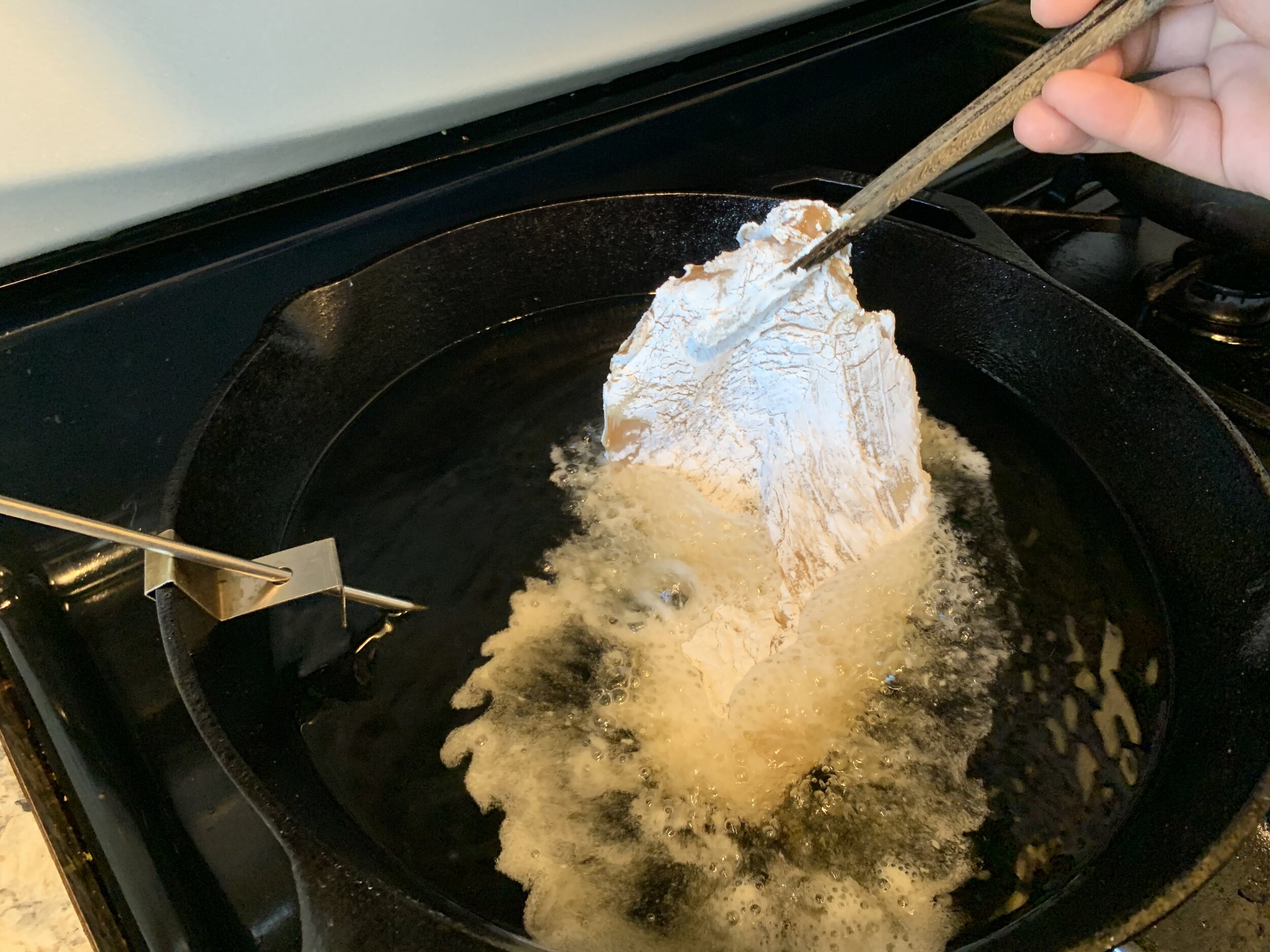

When all is ready, bring one inch of oil to 375° F in a cast iron pan or wide, heavy pot suitable for deep-frying. When the oil is up to temperature, begin breading and frying the chicken cutlets. We need to fry the cutlets in a single layer in the pan, so depending on how wide your pan is, we will be working one or two cutlets at a time, breading each cutlet immediately before frying it.

Dip the chicken cutlet in the egg mixture, flipping to coat both sides. Then dredge the cutlet in the sweet potato starch, again flipping to coat both sides. Shake off the excess—you are looking for a very thin coat of starch. Immediately place the coated chicken cutlet to the hot oil, laying the cutlet away from you to avoid splatter. Fry the cutlet for 2-3 minutes per side, flipping once. When flipping such a large piece of meat, be very careful to not drop the cutlet into the oil, again to avoid splatter. While frying the second side of the cutlet, you can start breading the next batch.

After a total of 5-6 minutes frying, the cutlets should be golden brown and crispy. Remove them from the hot oil, place them on the cooling rack, and immediately sprinkle with pepper salt. Continue breading and frying until all of the cutlets are cooked.

Serve the fried chicken cutlets with additional pepper salt for dipping. To make a “bian dang” style plate, serve the cutlets over rice with a fried or soy sauce egg, bok choy, and pickled cucumbers or daikon radish.

Substitutions

You can prepare thinly sliced pork loin cutlets using the same method. If you’d like your chicken to be a bit spicy, sprinkle some chili powder into the sweet potato starch before frying, or mix some cayenne or Sichuan pepper into your pepper salt. You can also add some garlic to the marinade if you’d like. If you can’t find sweet potato starch, you can substitute cornstarch, but the results are really not the same. You can buy sweet potato starch in some Asian supermarkets (Korean markets in particular usually will stock it), or find it online.

[1] Pai (排) is a Chinse word which means “slab of meat,” and is used in instances where English speakers might use the words “steak,” “chop,” or “cutlet.” As such, you will sometimes find this dish translated as “Taiwanese chicken steak.” Incidentally, “pai” is also the Chinese word for a raft.

[2] In the late 19th century, Japan imported large quantities of rolling stock and railway expertise from Great Britain. Japanese construction explains why in Taiwan—otherwise a right-hand drive country—the trains run on the left.

[3] Nationalist China received significant reconstruction aid from the United States after World War II, as part of the Asian equivalent of the Marshall Plan.

[4] In Japan, bento boxes sold on trains or at train stations are also known as ekiben (駅弁), or “railway meals.”

Recipe

Prep Time: 10 min Cook Time: 20 min Total Time: 1 hr

(+30 min inactive)

Difficulty: 3/5

Heat Sources: 1 burner

Equipment: cast iron pan or wide pot for deep frying, thermometer, sheet pan, cooling rack

Servings: 4

Ingredients

4 chicken breasts, butterflied

1 tbsp soy sauce

1 tbsp sesame oil

1 tsp cornstarch

1½ tsp white pepper

1 tsp flaky sea salt

1 egg

1 cup sweet potato starch

Vegetable oil

Instructions

1. Butterfly each chicken breast, cover with plastic wrap, and pound it with a meat mallet or pot to a thickness of ¼ inch.

2. In a small bowl, mix together the soy sauce, sesame oil, cornstarch, and ½ tsp white pepper to make the marinade.

3. Place the chicken cutlets in a plastic zipper bag, and pour over the marinade. Seal the bag, massage the meat to coat all of the pieces, and let marinate for 30 minutes to 1 hour.

4. Meanwhile, prepare the pepper salt by mixing together the flaky salt and 1 tsp white pepper. Set aside.

5. When the chicken is ready to cook, prepare your breading station. Beat together 1 egg and ½ cup water, and pour onto a large plate. On a second plate, place the sweet potato starch. Prepare a holding area for cooked chicken by placing a cooling rack on a sheet tray.

6. Bring a couple inches of oil to 375° F in a heavy pan suitable for deep-frying. When the oil is hot, dip a chicken cutlet in the egg mixture, flipping to coat both sides. Then dredge both sides with sweet potato starch, shaking off the excess. Carefully place the chicken cutlet into the hot oil, laying away from you to avoid splatter. Fry the chicken in a single layer, 1 or 2 pieces at a time, depending on the size of your pan.

7. Fry the chicken for 2-3 minutes per side, flipping once. Remove the cooked chicken to the cooling rack, and sprinkle with pepper salt (to taste) while still hot.

8. Repeat steps 6 and 7 until all of the chicken cutlets are cooked.