Taiwanese Beef Noodle Soup

台灣牛肉麵 (Taiwan Niu Rou Mian)

Taiwanese beef noodle soup is an iconic and comforting dish—noodles bathed in a rich and spicy broth, served with tender chunks of beef, vegetables, and herbs. It is perhaps Taiwan’s best known culinary export, and is considered by many to be the country’s national dish.[1] However, beef noodle soup is not a food endemic to the pre-World War II Taiwanese population. In fact, neither beef nor wheat noodles were commonly consumed on the island. Rather, this dish reflects influences from across China and the pressures of Taiwan’s history. The story of beef noodle soup is the story of the last 70 years of Taiwan reflected in a single bowl.

When the Republic of China (ROC) retreated to Taiwan at the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949, no one in the nationalist ranks believed that they would be staying for long. It was expected that with American backing, the war would go on, until one of two outcomes occurred—either Taiwan would be a staging point from which ROC forces could one day liberate the mainland, or the communists would soon invade in short order and finish the Kuomingtang off. In either case, the first priority was to establish military bases on the island from which ROC could fight.

The ROC Army, Navy, and Air Force all quickly established rough-and-ready bases scattered across the island. Around these bases sprung villages in which the base personnel and their families could live. These military villages, known as juan cun (眷村), were meant to be temporary structures, and were haphazardly constructed with cramped quarters.

American-built F-86 Sabre fighters of the ROC Air Force engaging communist MiG-15s over the Taiwan Strait in 1958.

The frequent violent clashes between ROC and the newly established People’s Republic of China (PRC) throughout the 50s certainly suggested to all concerned that the civil war could start up again in earnest at any minute. However, as the decades rolled by and the People’s Republic of China consolidated power on the mainland, the ROC had to confront the fact that they were on Taiwan to stay. The Kuomingtang ruled the island under martial law for nearly four decades, suppressing dissent and driving deep wedges between the “native” Taiwanese (including both aboriginal Taiwanese and Han Taiwanese living on the island prior to the war) and the “mainlanders” (Chinese who came to Taiwan in 1949).

During this time, the juan cun developed a tightknit culture of their own. Because they were built of families of military personnel, juan cun were almost exclusively composed of mainlanders, all exiled from their ancestral homes. For a long time, these literally gated communities remained isolated from their Taiwanese neighbors. Within the gates of the military villages, however, one found a melting pot of cultures from across China.[2] From this melting pot emerged many dishes now considered to be Taiwanese street stall staples, including potstickers, soup dumplings, you tiao, and, of course, beef noodle soup. Taiwanese beef noodle soup is clearly modeled on similar dishes found in the Sichuan Province of China, which feature rich and spicy broths. However, the wheat noodles used in the dish are more similar to the soup noodles eaten by the Chinese Muslims of Lanzhou Province.

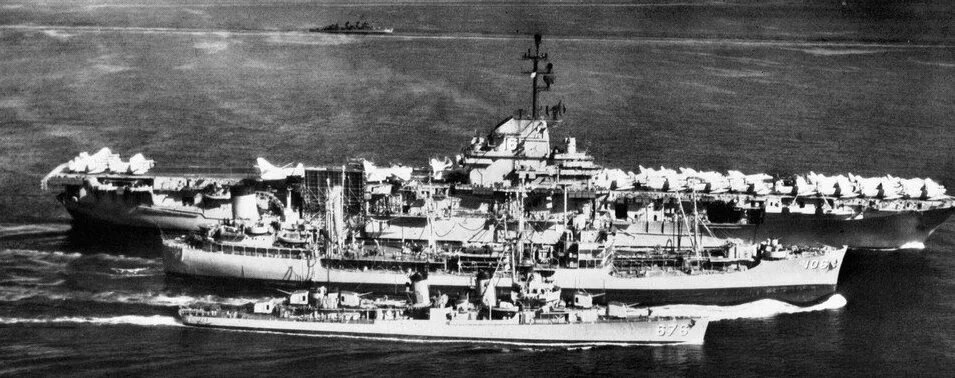

USS Lexington (CV-16) and her task force operating in defense of Taiwan in the 1950s.

Taiwanese beef noodle soup also bears the unmistakable marks of American influence. The United States had backed the Nationalist cause since 1939, and this close military affiliation continued throughout the Cold War. American materiel support flooded Taiwanese military bases, from supplies to small arms to fighter jets and tanks. USAF squadrons and advisors often operated from the island, and on countless occasions, the aircraft carriers of the US Navy were the only thing standing between Taiwan and invasion by the PRC. With the Americans came both American food and American food culture. Mainlanders from Northern China brought with them a taste for wheat-based food, but the tropical climate of Taiwan was unsuited to wheat cultivation. However, both wheat and beef could now be imported from the United States. The addition of tomatoes to the beef broth is another example of the influence of American tastes.

One of the remaining juan cun today, preserved as a museum near Hsinchu.

As Taiwan liberalized and democracy reasserted itself, the social divisions between the natives and mainlanders began to soften. The civil war generation retired from military service and drifted into civilian life, taking their food with them. Veterans began selling beef noodle soup in street stalls across the country, and the popularity of the dish exploded. Beef noodle soup was one of the first foods to drift outside the walls of the military villages and into the Taiwanese mainstream, and its popularity helped to break down the walls separating mainlanders and natives.

With a new generation of Taiwan-born men and women in military uniform, the juan cun began to lose their unique cultural identity. The temporary structures fell into disrepair, and many were bulldozed to make way for modern housing developments. Today, few juan cun remain in Taiwan, with a handful preserved as historical sites. The historical legacy of the juan cun remains divisive to this day. On one hand, it is easy to empathize with their inhabitants, torn from their ancestral homes and extended families, living in a new land in cramped quarters, with only each other and their common ideals to sustain them and carry on the fight. On the other hand, it is important to recognize that for many years, those who lived within the walls of military villages held many privileges denied to other Taiwanese, and wielded greater political power than their neighbors. It is undeniable that the juan cun have had an outsized influence on modern Taiwanese culture, and on food culture in particular.

To some, the prevalence of beef noodle soup on the Taiwanese food scene, at the expense of older and more traditional Taiwanese foods, is an example of the dominance of mainlander culture in Taiwan.[3] Perhaps more optimistically, however, the story of beef noodle soup is a salient example of the capacity of food to build bridges between people. Often, the food of a foreign culture will find acceptance in a new land before the people of that culture do. Food has the power to break down cultural barriers. It can remind us that ultimately people are searching for the same things, and can help us empathize with other cultures. In a good bowl of Taiwanese beef noodle soup, you can find the story of a people looking for comfort in the memory of a homeland they can never return to. You can find the story of people adapting to a new world and finding their place in it. And you can find the story of a nation attempting to move beyond the divisions of its history and celebrate its unique place in the world. Those are all good lessons to take from a bowl of noodle soup.

Ingredients

1 lb Taiwanese braised beef

4 cups beef braising liquid

1 lb thin Asian wheat noodles

1 tomato, chopped

1 tbsp tomato paste

1 tbsp doubanjiang

5 oz bok choy

1 tsp Sichuan pepper

1 bunch cilantro

4 oz pickled mustard greens, chopped

1 tbsp Chinkiang vinegar

This dish is built on our Taiwanese braised beef recipe, and calls for both the braised beef and 4 cups of the braising liquid. Add the braising liquid to a pot and bring to a boil. Add to the broth the chopped tomato, together with 1 tablespoon tomato paste. The tomato paste is a bit of a cheat which quickly adds more depth to the tomato flavor of the soup. Next, add 1 tablespoon of doubanjiang (豆瓣醬) to the soup. Doubanjiang is a savory paste made from fermented soybeans, and is packed full of umami. Doubanjiang is available in both plain and spiced varieties. We will be calling for a spicy one in this dish—you can adjust the heat level by changing the amount or the brand you’re using.

Stir the soup to incorporate these ingredients, and simmer the broth, covered, for 15 minutes to let the flavors develop. While the broth simmers, we can prepare the vegetables. Wash the bok choy, and separate it into individual leaves. We will be cooking these in the soup later. The other vegetable usually served with beef noodle soup is suan cai (酸菜), or preserved mustard greens. These greens have been brined and fermented in a fashion similar to sauerkraut, and have a distinctive sour flavor. Because of the brine, suan cai is too salty to eat straight from the package. Instead, chop the pickled vegetable into strips and place the strips into a bowl of cold water to soak. Soaking the suan cai for about 10 minutes in clean water will wash out much of the salt.

In a second pot, bring some salted water to a boil. While it is most traditional to use thin wheat noodles for this noodle soup, you can use any Asian wheat noodle in the dish. Cook the noodles according to package instructions. We want the noodles to be done at the same time the soup is done, so time the start of your noodles appropriately. Most noodles should take about 10 minutes to cook through, so they should hit the water when the broth has already been simmering for 10 minutes.

After the broth has simmered for 15 minutes, add the braised beef pieces to the soup to warm through. Add the bok choy leaves to the soup as well, and continue to simmer for 5 more minutes, or until the bok choy leaves are tender.

When the soup is ready, turn off the heat and stir in 1 tablespoon Chinkiang vinegar. The noodles should be done at about the same time. Drain the noodles and place them into serving bowls. Ladle over the hot beef broth, making sure that each bowl gets a couple pieces of beef and some bok choy leaves. Drain the pickled mustard greens, and top each bowl with some of the mustard greens, cilantro leaves, and a pinch of Sichan pepper. Serve the noodle soup immediately, with chili oil and Chinkiang vinegar at the table!

Substitutions

If you don’t have doubanjiang, you can substitute Korean gochujang. If you prefer a spicier broth, add fresh or dried red chilies to the broth with the tomatoes. If you don’t like cilantro, you can substitute them for chopped scallions.

[1] The capital city, Taipei, hosts an annual Beef Noodle Festival, where chefs and restaurants compete for the title of best beef noodles of Taiwan.

[2] For those looking to better understand the exodus of 1949 and the culture of juan cun villages, I recommend the award-winning period drama, “A Touch of Green,” which is currently available on Netflix. The show follows a community of Republic of China Air Force pilots and their families from 1945 to 1970 as they bear the hardships of World War II, the end of the civil war and exile to Taiwan, and the White Terror. It also explores the ROCAF’s longstanding close relationship with the United States Air Force, and the dangerous Black Bat and Black Cat missions flown by the Taiwanese during the Cold War on behalf of the CIA.

[3] Another oft-cited case of this is Din Tai Fung, the Michelin-starred Taiwanese restaurant, which specializes in Chinese Huaiyang cuisine.

Recipe

Prep Time: 10 min Cook Time: 20 min Total Time: 30 min

Difficulty: 2/5

Heat Sources: 2 burners

Equipment: 2 pots

Servings: 4

Ingredients

1 lb Taiwanese braised beef

4 cups beef braising liquid

1 lb thin Asian wheat noodles

1 tomato, chopped

1 tbsp tomato paste

1 tbsp doubanjiang

5 oz bok choy

1 tsp Sichuan pepper

1 bunch cilantro

4 oz pickled mustard greens, chopped

1 tbsp Chinkiang vinegar

Instructions

1. In a pot, bring the braising liquid to a boil. Add the chopped tomato, tomato paste, and doubanjiang to the pot and stir well. Simmer the broth, covered, for 15 minutes.

2. While the broth simmers, wash the bok choy leaves. Chop the pickled mustard greens and place them in a bowl of cold water to soak.

3. Bring a pot of salted water to a boil. Cook the noodles according to package instructions. The noodles will usually need to cook for about 10 minutes, so you should put them into the water when the broth has already been simmering for 10 minutes, so both elements finish at the same time.

4. After the broth has simmered for 15 minutes, add the braised beef pieces to the soup to warm through. Add the bok choy leaves and cook until the bok choy is tender, about 5 minutes.

5. When the soup is ready, turn off the heat and stir in 1 tbsp Chinkiang vinegar.

6. When the noodles are done, drain them from the water and place into serving bowls. Ladle over the beef broth, making sure that each bowl gets a couple pieces of beef.

7. Drain the pickled mustard greens. Top each bowl with some bok choy, pickled mustard greens, fresh cilantro leaves, and a pinch of Sichuan pepper. Serve immediately.