Steak au Poivre

Black pepper is a ubiquitous seasoning in many modern kitchens, but is rarely given the spotlight, generally relegated to a supporting role in the cast of flavors in a dish. Steak au poivre is an exception to this rule, a hearty dish in which pepper plays a leading role. The dried fruit of a plant native to the Kerala region of India, pepper has been paired with red meat since ancient times. The Apicius manuscript, a collection of Mediterranean dishes which dates to Imperial Rome, discusses at length the ability of large quantities of black pepper to mask the smell of old meat.[1] With the decline of robust trade links between Western Europe and South Asia after the collapse of Rome, pepper became an expensive luxury item in medieval kitchens, with only the very wealthiest able to afford to pepper crust a piece of meat. It was not until the opening of the sea routes to Asia that pepper once again became widely available in Europe. 18th century European and American cookbooks include recipes for pepper-crusted venison, a de-boned piece of meat liberally coated with cracked black pepper and then seared. In this application, pepper is being used to help mask the gamey flavor of venison, and the quick sear keeps the lean piece of meat tender. In early 20th century France, the substitution of lean beef tenderloin for venison and the addition of a cream sauce to help cut the heat of the peppercorns resulted in the modern version of pepper-crusted steak—steak au poivre, or “pepper steak.”[2] In America, steak au poivre can still be found on steakhouse menus, but with the right technique and ingredients, it is easy to prepare at home for a fraction of the cost.

Ingredients

4 tenderloin steaks (6 oz, 1 in thick)

2 tbsp black pepper, crushed

1 tbsp salt

2 tbsp butter

1 tbsp olive oil

1 clove garlic

1 shallot, minced

½ cup beef stock

½ cup cognac

1 cup heavy cream

We will be using beef tenderloin fillets for this recipe, a very lean cut with small amounts of connective tissue. Tenderloin is one of the priciest cuts of beef, but can often be found for a reasonable price at wholesale clubs such as Costco. Slice the tenderloin crosswise into pieces approximately 1 in thick. Though the exact thickness is not that critical, it is important to ensure that all the pieces you plan on cooking are the same thickness, so that they will cook with consistent timing. Pat the steaks dry, then salt all sides and let the steaks sit at room temperature for 30 minutes. This allows the internal temperature to rise slightly before cooking, allowing the meat to cook more gently and evenly when it hits the pan. The risk of pathogens from leaving the steaks at room temperature for this amount of time is minimal, as only the surface is exposed to the outside environment, and that surface has been liberally salted and is about to be exposed to high heat.

While the steaks come to room temperature, prepare the black pepper. We want large pieces of peppercorn, so use a mortar and pestle to crack the peppercorns, or use a pepper grinder on its coarsest setting. If neither of these are an option, place the peppercorns in a sealed plastic zipper bag, then bash them with a rolling pin. Pour the black pepper onto a small plate or shallow bowl large enough to accommodate one steak at a time. Also while the meat is coming to temperature, mince the shallot and set aside for later use.

After 30 minutes of resting, dust the excess salt from the steaks and press each side of each steak into the black pepper. We are looking for a thick, uniform coat of pepper on both sides of the steak. When all the steaks are coated, we are ready to sear.

Before we discuss cooking this cut in particular, let us step back a bit and discuss basic principles. When it comes to cooking large pieces of meat, regardless of the animal, cuisine, flavor, or cut, the primary objective is generally to achieve tenderness, while a common secondary objective is to create a crusty exterior with a pleasant texture. What we perceive as a tender mouthfeel has two components: short muscle fibers and moisture. For some cuts, the direction of slicing the meat for service is critical because the angle of the slice directly impacts the length of the muscle fibers you experience when chewing. In tenderloin this is not an issue because the tenderloin muscle does little work in the animal and thus has almost no connective tissue.

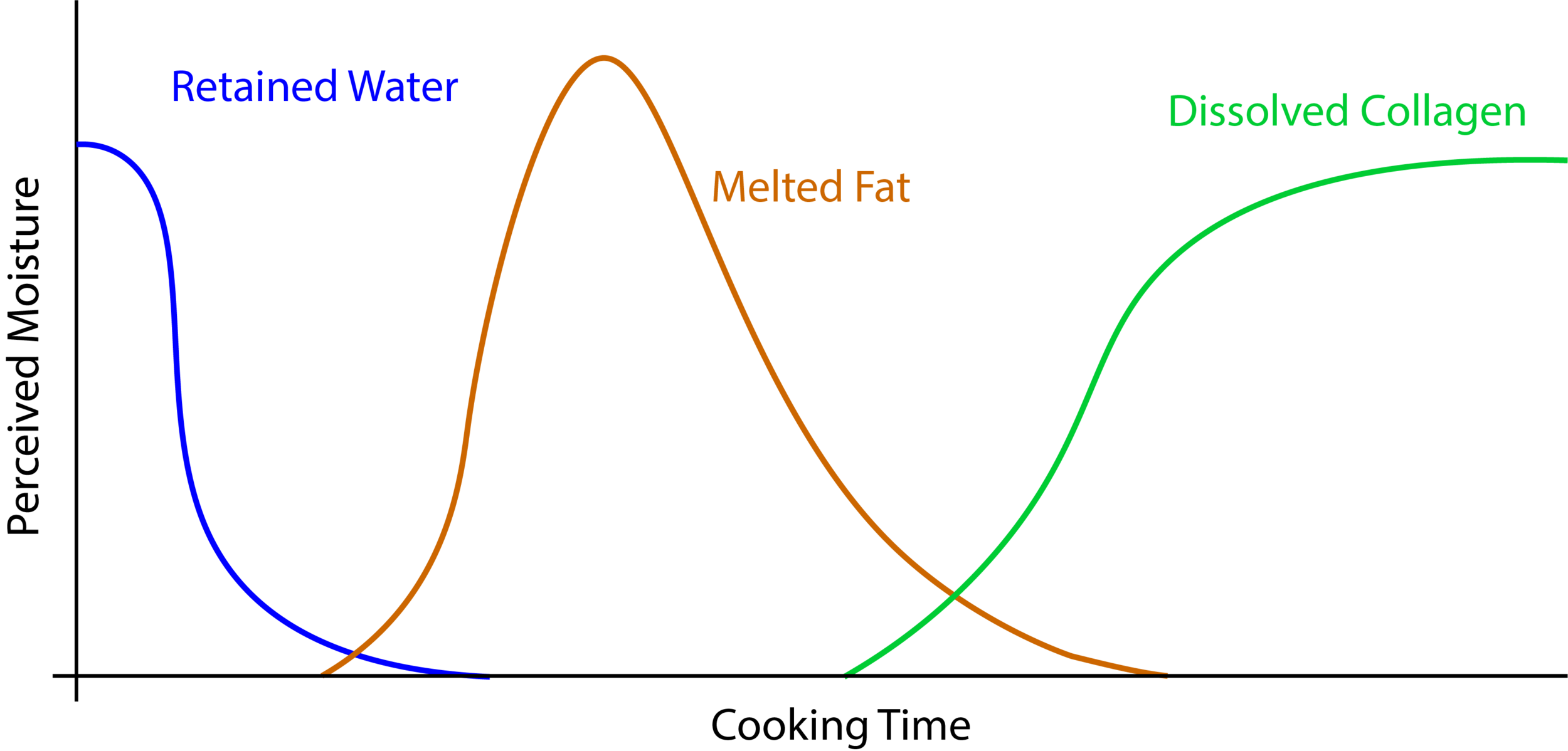

Moisture is trickier. In meat, moisture can come from one of three sources: 1) water content of the muscle initially, 2) melting fat around or marbled within the muscle, 3) dissolved collagen from connective tissue. In most cases, these three sources are temporally segregated. As you apply heat to a cut of meat, the water content is liberated rapidly through evaporation, leaving the meat dry if overcooked. As you continue to cook it, fat will begin to melt, but cook it for even longer and the fat will render and leave the meat. Continue to cook it and any connective tissue will break down, dissolving the collagen and forming gelatin. Because of these different sources of moisture, most cuts have an ideal cooking method. For example, brisket has a large amount of connective tissue which is tough to eat unless completely dissolved, making it a common cut for low, slow methods such as braises and barbecues. Cuts with a large amount of fat and little connective tissue, such as ribeye or chicken thighs, do well when cooked to the point fat begins to melt. The least forgiving type of moisture to hold onto is water, as it is easily driven away. For lean cuts with no connective tissue, such as chicken breast, this is the only type of moisture we have available.

Because tenderloin has relatively little fat and no connective tissue, we are definitely in the water moisture regime. The strategy is therefore to cook it hot and fast, for as little time as possible. To accomplish this, it is important to use a pan capable of reaching and holding on to high heat. This means that we are reaching for stainless steel or cast iron. Nonstick pans will not work for this recipe, as not only will they not safely reach the high temperatures required, they will also drop rapidly in temperature when the meat is introduced. A secondary consideration is also that a nonstick pan will not generate a fond as effectively, making it difficult to construct a pan sauce.

Finally, let’s talk doneness. While very home cook and consumer is at liberty to choose whatever degree of doneness they desire in a steak, it is undeniably true that some cuts benefit from longer cooking, while others don’t. For tenderloin in particular, because of the aforementioned race against the forces of capillary action and evaporation, I strongly recommend that you do not take this cut beyond medium rare. Cooking a tenderloin past this points results in chewy, dry meat. If you insist on having steak au poivre that is medium or medium well, I’d recommend using a different cut for your preparation, such as strip or sirloin, which will both be cheaper and taste better at that doneness.

How can you judge doneness? Times and heats will vary based on your cooktop, pan, and steak, so when cooking meat of any kind, always consider that information to be a guideline only. One commonly used method to judge the doneness of a steak is to gently poke the meat with a clean finger as it cooks, and judge the doneness by how springy the meat is. This is a decent method to ballpark doneness if you have extensive experience, but requires a great deal of practice, and the feel can vary from cut to cut. The color of the interior of a steak is not a reliable indicator either, as color can vary greatly from animal to animal and cut to cut. The bulletproof method of judging doneness is a probe thermometer. To check doneness, insert an instantaneous probe into the center of the steak and take its temperature. Remember that after you remove a steak from the heat, the temperature will continue to climb by several degrees as it rests. For medium rare and for a cut of this size, the target internal temperature in the pan is 125° F. The steak will likely coast up to a service temperature of 130° F when resting.

With the theory lesson over, it’s back to cooking. Add 1 tablespoon of butter and 1 tablespoon of olive oil to the pan over medium-high heat, and let the butter melt. Bruise the clove of garlic and add it to the pan to infuse the oil. When the fat just starts to smoke, it is time to add the steaks to the pan.[3] Lay the steaks into the hot oil away from you to avoid oil splatter, positioning the steaks evenly in the pan. Once they are in the pan, do not move them until you are ready to flip. Sear the steaks over medium-high heat for about 4 minutes, then flip and sear the other side for another 4 minutes, or until a thermometer reads an internal temperature of 125° F. Remove the steaks from the heat and loosely cover with tinfoil, allowing them to rest.

Reduce the heat to medium and remove the garlic clove. Add the minced shallot to the pan and cook, stirring occasionally, for about 2 minutes, until the shallots soften.

Once the shallots are soft, it comes time to introduce the cognac to the heat. Cognac is a major flavor component of the sauce for steak au poivre, and is also a primary source of theatre when the dish is prepared tableside at restaurants. With an alcohol content of 40%, cognac produces an abundance of alcohol fumes when it hits the hot pan, fumes that can be ignited to create bright, vivid flames. If you want to experience the pyrotechnics of a flambé and are comfortable and confident that you can control the fire, feel free to do so, either igniting the alcohol fumes with flames from the burner, or using a firestarter (be sure to have a fire extinguisher nearby, just in case). The flambé, however, is entirely theatrical, and does nothing to influence the final flavor or texture of the dish. If you don’t want the flames, then it is best to turn the burner off before introducing half a cup of cognac to the pan. Don’t use the expensive stuff here—V.S. grade is perfectly adequate. Stir and scrape the bottom of the pan, dissolving the fond—the brown bits of meat and pepper sticking to the pan. After 30 seconds or so, after the initial fumes have subsided, turn the heat back on to medium, add half a cup of beef stock, and bring to a simmer.

Follow the beef stock with a cup of heavy cream, stir, and again bring the sauce to a simmer. Reduce the sauce slowly until it coats the back of a spoon, a consistency the French define as nappe. At this point, remove the sauce from heat, and stir in 1 tablespoon of cold butter. A common technique for finishing sauces and soups in French cuisine, this final hit of butter gives sauces a visual shine and more velvety mouthfeel. If you are trying to reduce the amount of fat in this dish, you can skip this step.

Season the sauce with salt and pepper to taste, remembering that it will be served with a salted and heavily peppered steak. Then serve the steaks with the cream sauce. Traditional side dishes include asparagus and roasted or fried potatoes.

Substitutions

This dish can be prepared with other boneless or deboned cuts of steak, though the cooking time may have to be modified accordingly. Other common cuts to use for this dish include entrecote, strip steak, and sirloin.

For a more subtle flavor, you can use white peppercorns rather than black peppercorns. Alternatively, you can use a mix of red, black, and white peppercorns.

Substitutions for cognac include other brandies or whiskey. You can also choose to use a red wine instead, which will give the sauce a different flavor profile. You can substitute leeks for shallots in the sauce, or choose to leave them out entirely. Some variations on the cream sauce include the addition of tarragon or Dijon mustard. Substituting heavy cream for crème fraiche can add a sour tang to the sauce.

[1] It is unclear who wrote or assembled the Apicius manuscript, but historians are fairly certain that it was not a man named Apicius. There was a minister during the reign of Emperor Tiberius, Marcus Cavius Apicius, who was well known for his luxurious tastes. As a result, the name “Apicius” had entered the Roman vernacular as a gourmet or glutton, similar to how we might use “Einstein” in modern vernacular English to refer to someone who we think is smart. After the fall of the Roman Empire, Latin written works in Western Europe were preserved in monasteries, the monks writing out the work anew once every generation. In the game of telephone that was medieval manuscript copying, this subtle reference was lost, and the work came to be attributed in many cases to a fictional man named Caelius Apicius, a mistake that gets perpetuated to this day in insufficiently researched food writing.

[2] There is some disagreement about which chef and restaurant originated the dish, with four distinct restaurants laying claim to the creation of steak au poivre. Interestingly, three of the four stories involve catering to drunk American expats whose taste buds were so deadened by cocktails that a large amount of pepper was required for them to taste the steak. Whether that bit of the story is apocryphal or not shall be left for the reader to decide.

[3] It is often said that mixing oil and butter together raises the smoke point compared to butter only, but this is a myth. After all, if something in the butter (milk proteins) burns at a certain temperature, whether it’s floating around in milk fat or olive oil is not going to change the required environmental activation energy. However, there are other advantages to mixing fats for searing, particularly in the flavor and color departments. For more on debunking this food myth, refer to this article from Kenji Lopez-Alt.

Recipe

Prep Time: 5 min Cook Time: 20 min Total Time: 50 min

(+30 min inactive)

Difficulty: 3/5

Heat Sources: 1 burner

Equipment: skillet (steel or cast iron), probe thermometer (optional)

Servings: 4

Ingredients

4 tenderloin steaks (6 oz, 1 in thick)

2 tbsp black pepper, crushed

1 tbsp salt

2 tbsp butter

1 tbsp olive oil

1 clove garlic

1 shallot, minced

½ cup beef stock

½ cup cognac

1 cup heavy cream

Instructions

1. Season steaks with salt on both sides, and let them air dry at room temperature for 30 minutes.

2. Crush or coarsely grind the black pepper onto a small plate, then press each side of each steak into the pepper, coating each side liberally and evenly.

3. Heat the olive oil and 1 tbsp of butter in a large skillet or cast iron pan over medium-high heat. As soon as the fat begins to smoke, add the steaks to the pan. Sear over medium-high heat for 4 minutes per side (medium rare), or to your desired doneness.

4. Remove the steaks from the heat and let rest. The target internal temperature for medium rare is 125° F in the pan, which will coast up to a service temperature of 130° F while resting.

5. Turn the pan down to medium heat, add the minced shallot, and cook, stirring, for 2 minutes, until the shallots soften.

6. Turn the burner off and deglaze the pan with the cognac, stirring and scraping the bottom of the pan to dissolve the fond. After 30 seconds, return the pan to medium heat, add the beef stock, and bring to a simmer.

7. Whisk in the cream and simmer the sauce until it reduces to nappe consistency, coating the back of a spoon. Remove the sauce from the heat, whisk in the remaining tbsp of butter, and season with salt and pepper to taste.

8. Serve the rested steaks with the cream sauce.